--I am okay with the old-fashioned formality that used to attach to the doctor-patient relationship. I want my doctor to be authoritative and wise, and to the extent that calling him “Doctor” furthers this notion, I am not put off. I don’t want to be his friend. I don’t want to call him “Todd.”

--Doctors are explorers, mapping uncharted land. They are 49ers, prospecting in faraway territory for something priceless and elusive. Doctors are spelunkers. (“Let’s go down there! And bring a camera!”)

--At a certain point in your life, you are going to end up entrusting your physical health to someone who was riding a Big Wheel during the Reagan Administration. At first it seems fabulously risky, but you get used to it. It is a strange rite of passage, one of the first times you are able to acknowledge that someone younger knows more than you do.

--It is impossible not to look at other people in the waiting room and wonder what is wrong with them.

--I wish the nurse who takes my blood pressure would stop talking about her son who is doing Jazz Studies at Chico.

--On the exam room wall: graphic illustrations of normal sinus cavities, written exhortations to get your colonoscopy, a sign reminding all health-care practitioners to wash their hands. There is nothing to read except a back issue of “Modern Maturity.” I don’t read it because it might be germ-y: a sick person might have touched it last. In doctors’ offices, I push open doors with my shoulder and slather anti-bacterial cleanser on my hands when I get back to the car.

-- It is inordinately important to me that my doctor believe I am smart. I am sure this has something to do with the fact that my father was a doctor. (I couldn’t care less what my accountant thinks of me.) When he says, That’s a good question, I beam. It is just nuts.

--I never take the elevator at the doctor’s, if I can help it. Germ-y air.

--I love my doctor, but I am always so relieved to be finished talking to him. Is there another person in my life I feel this way about? Can’t think of one.

--A lot of people are sick. A lot. It is easy to forget this if you and your family are healthy. When you go to the doctor’s, you are immediately reminded. It is touching and sobering. I hate being sick more than anything. (The only thing worse is when my kids are sick.) Going to the doctor’s makes me want to be compassionate and kind. I want to hug all those people in the waiting room and tell them it will be all right, except that, of course, I don’t know that it will be all right. (And also, the germs.) For some of us, it will be, and for some of us, it won’t. And that is just brutally awful, something I never get used to.

--A lot of things I go to the doctor for are things people died of seventy years ago. Now there are new drugs and therapies and technologies. It makes you think of all the things we are still dying of that someone will someday cure. Who is she, and what is she doing now? Probably sitting at the kitchen table, coloring.

Wednesday, April 21, 2010

Friday, April 2, 2010

Genius

I am reading Nicholson Baker’s new book, The Anthologist, and finding it wonderfully entertaining. Every night I look forward to getting into bed and diving in. It is like having a conversation with a funny, damaged, massively literate friend.

Nicholson Baker is a remarkable writer. I am certainly not the first person to say so, but I may be one of the first people to have recognized it. He was in a creative writing class I took in college. (I attended a women’s college, Bryn Mawr, which has a cooperative relationship with Haverford College, where Baker went.) I noticed him on the first day of the semester. He was very tall and very handsome, and I had never seen him before (which was noteworthy in and of itself: the two colleges were quite small and “tall and handsome” [at the same time] was a rare and highly visible attribute among Haverford men).

The class was taught by Christopher Davis, who told us that each of us would be required to submit eight pages (I think) of fiction, which would then be critiqued in class. I set confidently to work and produced a short story called “Summer on Goose Island.” Just writing the name fills me with horror. It was the story of a Tragic marriage, with lots of fog-swept sand dunes and execrable dialogue. I was rightly eviscerated in class for its many flaws, none of which I remember, as I threw the story away immediately on returning to my dorm room.

What I do remember, though, was being handed Nicholson Baker’s writing sample. It was twenty-six pages long and I thought, Oh, good Lord. I imagined that it was going to be an obvious attempt at suck-up-ery, that this Nicholson Baker, whoever he was, thought that twenty-six pages was his sure-fire route to an ‘A’.

I don’t remember what he wrote. I just remember that on page six, I looked up and said to my boyfriend, Oh, my God.

I don’t recall how the story was critiqued. I think Christopher Davis knew that he was in the presence of greatness. Nobody said much, except another Haverford student who made an ass out of himself by saying that the story “took too long to get going.” (There is one of these in every writers’ critique group I have ever been in.) Nicholson Baker didn’t say a word. He nodded and made a few notes.

After class, I went over to him and babbled something about how he was a genius. He smiled politely and said, “Thanks very much.” In that instant, I knew that Nicholson Baker was destined to travel in circles different from those I would inhabit. He was already a grownup, albeit with talents and sensibilities very few grownups possess. I knew that I wanted to be a writer; I knew that I was probably good enough to become one. But I also knew that I would never approach the deft, sure-handed brilliance that Nicholson Baker effortlessly commanded at the age of twenty.

It’s okay. I’ve accepted it.

Some people are just that good. And what I learned by being in class with Nicholson Baker is that most of us are not. Most of us have to work really, really hard and be very, very lucky.

And isn’t that just the greatest name for a writer? How did his parents know?

Nicholson Baker is a remarkable writer. I am certainly not the first person to say so, but I may be one of the first people to have recognized it. He was in a creative writing class I took in college. (I attended a women’s college, Bryn Mawr, which has a cooperative relationship with Haverford College, where Baker went.) I noticed him on the first day of the semester. He was very tall and very handsome, and I had never seen him before (which was noteworthy in and of itself: the two colleges were quite small and “tall and handsome” [at the same time] was a rare and highly visible attribute among Haverford men).

The class was taught by Christopher Davis, who told us that each of us would be required to submit eight pages (I think) of fiction, which would then be critiqued in class. I set confidently to work and produced a short story called “Summer on Goose Island.” Just writing the name fills me with horror. It was the story of a Tragic marriage, with lots of fog-swept sand dunes and execrable dialogue. I was rightly eviscerated in class for its many flaws, none of which I remember, as I threw the story away immediately on returning to my dorm room.

What I do remember, though, was being handed Nicholson Baker’s writing sample. It was twenty-six pages long and I thought, Oh, good Lord. I imagined that it was going to be an obvious attempt at suck-up-ery, that this Nicholson Baker, whoever he was, thought that twenty-six pages was his sure-fire route to an ‘A’.

I don’t remember what he wrote. I just remember that on page six, I looked up and said to my boyfriend, Oh, my God.

I don’t recall how the story was critiqued. I think Christopher Davis knew that he was in the presence of greatness. Nobody said much, except another Haverford student who made an ass out of himself by saying that the story “took too long to get going.” (There is one of these in every writers’ critique group I have ever been in.) Nicholson Baker didn’t say a word. He nodded and made a few notes.

After class, I went over to him and babbled something about how he was a genius. He smiled politely and said, “Thanks very much.” In that instant, I knew that Nicholson Baker was destined to travel in circles different from those I would inhabit. He was already a grownup, albeit with talents and sensibilities very few grownups possess. I knew that I wanted to be a writer; I knew that I was probably good enough to become one. But I also knew that I would never approach the deft, sure-handed brilliance that Nicholson Baker effortlessly commanded at the age of twenty.

It’s okay. I’ve accepted it.

Some people are just that good. And what I learned by being in class with Nicholson Baker is that most of us are not. Most of us have to work really, really hard and be very, very lucky.

And isn’t that just the greatest name for a writer? How did his parents know?

Friday, March 26, 2010

The Office

I love seeing pictures of the places where writers work. Perhaps this is because I’m basically nosy and like seeing the insides of people’s houses.

My office is at the back of the house, shoddily added on by the previous owners, who neglected to provide access to heat. In the winter, I usually work upstairs or in front of the living room fireplace, where it is warmer.

In its favor, my office does have high ceilings and a bay window.

Here it is:

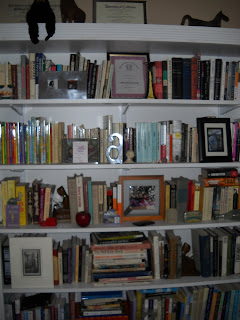

Bookshelves make a room. I need more:

Bookshelf detail: Galsworthy, a tiny picture of Big Ben, a bust of Dickens, a Pabst Beer opener from Robert commemorating one of our first dates:

Here’s my desk:

Desk details: my Bryn Mawr mug full of pens and pencils:

A spider made for me by a fan of Spider Storch, made at a reading at Cal State Fullerton:

Some of my inspirers: John Updike, my kids when they were babies:

The couch, where I work when the desk chair gets uncomfortable:

Sometimes I write at a local coffee shop, just to get out of the house. Great people watching, great hot chocolate, and there’s heat. But even if I’ve worked there, I like to spend a little time in my office every day anyway. It’s where I can be in the presence of pictures of my kids, vacation souvenirs, my favorite books.

Room of one’s own and all that.

My office is at the back of the house, shoddily added on by the previous owners, who neglected to provide access to heat. In the winter, I usually work upstairs or in front of the living room fireplace, where it is warmer.

In its favor, my office does have high ceilings and a bay window.

Here it is:

Bookshelves make a room. I need more:

Bookshelf detail: Galsworthy, a tiny picture of Big Ben, a bust of Dickens, a Pabst Beer opener from Robert commemorating one of our first dates:

Here’s my desk:

Desk details: my Bryn Mawr mug full of pens and pencils:

A spider made for me by a fan of Spider Storch, made at a reading at Cal State Fullerton:

Some of my inspirers: John Updike, my kids when they were babies:

The couch, where I work when the desk chair gets uncomfortable:

Sometimes I write at a local coffee shop, just to get out of the house. Great people watching, great hot chocolate, and there’s heat. But even if I’ve worked there, I like to spend a little time in my office every day anyway. It’s where I can be in the presence of pictures of my kids, vacation souvenirs, my favorite books.

Room of one’s own and all that.

Thursday, March 18, 2010

Coq Au Vin, Creativity, and What Aline Hallenbeck Said To Me In Eighth-Grade Home Ec

Our friends Roy and Josine came down for drinks, dinner, and Rummy-O today. I made coq au vin, which always makes me feel as though I should be wearing an apron with frills and pockets, like the one I made in Mrs. Nebeker’s eighth-grade home ec. class in 1970. (Note: I almost failed this class. I massacred that apron. Aline Hallenbeck said she didn’t like my hair color [brown] with my eye color [brown]. Barbara Lamon gave an oral report about skin care and could not utter the word “pimple” without dissolving. All in all, a massively stressful experience.)

When I tell people I’m not creative, they often say, But you write books! You must be creative. It’s a reasonable thing to think. I would say it to writers if I weren’t one. But because I am, I know that writing is a supremely laborious task bearing little resemblance to what I think of as creativity. There are no sparks of inspiration, no bursts of epiphanic realizations. (Well, very few, anyway.) There is just sitting and typing out a sentence and then deleting a word or a comma and sitting again. The process is “creative” only in the sense that something eventually gets made. But I, myself, am no more creative than the person who “makes” a spreadsheet or a diagnosis or a driveway.

Now, entertaining: that’s creative. I get to cut and arrange flowers,

design a menu (coq au vin over egg noodles, buttered green beans, blueberry crisp with vanilla ice cream) and cook it, pick the music (Benny Goodman, Marvin Gaye, Ray LaMontagne), and choose which china and napkins and wineglasses to use:

On thinking it through, I guess entertaining feels creative because it’s fun. Writing feels like a job. An important job—a job I adore, a job I think is vitally important, a job I am lucky to have—but a job. It’s slow-moving, often financially unrewarding. Not as stressful as having my appearance critiqued in eighth-grade home ec., but stressful nonetheless.

(Aline and I eventually became friends. She spent three hours on the phone with me one night in eleventh grade trying to get me to join Young Life and never held it against me when I chose not to. I’m not sure what the moral of this story is. The horrors of eighth grade don’t last forever? First impressions aren’t always accurate? Hair- and eye-color preferences change over time?)

At any rate, Roy and Josie and Robert and I had a blast playing Rummy-O.

A night with good friends can do much to revive one’s midweek spirits.

I’ll bet Aline Hallenbeck is a killer Rummy-O player.

When I tell people I’m not creative, they often say, But you write books! You must be creative. It’s a reasonable thing to think. I would say it to writers if I weren’t one. But because I am, I know that writing is a supremely laborious task bearing little resemblance to what I think of as creativity. There are no sparks of inspiration, no bursts of epiphanic realizations. (Well, very few, anyway.) There is just sitting and typing out a sentence and then deleting a word or a comma and sitting again. The process is “creative” only in the sense that something eventually gets made. But I, myself, am no more creative than the person who “makes” a spreadsheet or a diagnosis or a driveway.

Now, entertaining: that’s creative. I get to cut and arrange flowers,

design a menu (coq au vin over egg noodles, buttered green beans, blueberry crisp with vanilla ice cream) and cook it, pick the music (Benny Goodman, Marvin Gaye, Ray LaMontagne), and choose which china and napkins and wineglasses to use:

On thinking it through, I guess entertaining feels creative because it’s fun. Writing feels like a job. An important job—a job I adore, a job I think is vitally important, a job I am lucky to have—but a job. It’s slow-moving, often financially unrewarding. Not as stressful as having my appearance critiqued in eighth-grade home ec., but stressful nonetheless.

(Aline and I eventually became friends. She spent three hours on the phone with me one night in eleventh grade trying to get me to join Young Life and never held it against me when I chose not to. I’m not sure what the moral of this story is. The horrors of eighth grade don’t last forever? First impressions aren’t always accurate? Hair- and eye-color preferences change over time?)

At any rate, Roy and Josie and Robert and I had a blast playing Rummy-O.

A night with good friends can do much to revive one’s midweek spirits.

I’ll bet Aline Hallenbeck is a killer Rummy-O player.

Saturday, March 13, 2010

Of Good Conversation and Grace Under Pressure

I think we’re hungry for good conversation. For too many years, we’ve been watching the Kardashian sisters spew drivel and “real” housewives gossip and whine like nine-year-olds. Late-night talk shows used to provide a forum for intelligent, witty banter, but now, often, the guests are there simply to hawk a movie they’ve made. Their ulterior motives show; they aren’t up for an interaction that is both revealing and entertaining. If they are under twenty-five, they aren’t capable of it.

People don’t know how to talk well these days. I don’t mean “speak well,” i.e., use proper grammar and words appropriate to context. I mean they don’t know how to engage in discourse. There is an art to conversation, to sustaining a rhythm that includes equal measures of self-revelation, interest in the topic at hand, and genuine concern for what other participants have to say. I worry that it is dying, that the only people left talking on television will be bickering reality-show contestants and tongue-tied celebrity nitwits.

I may have to watch sports (with the sound off).

**

On the book front: During the holidays, I received from Bryn Mawr classmate and friend Maureen ’78 A VERY PRIVATE EYE, a memoir (told in journal entries and letters) by British author Barbara Pym. Wonderful! Descriptions of 1930s Oxford, trips to pre-War Germany, conversations with literate friends (see above). I enjoyed the memoir so much that I went out and bought one of Pym’s novels, A GLASS OF BLESSINGS. (All of Pym’s books have marvelous titles.) Also wonderful. Pym is often described as a sort of mid-20th-century Jane Austen, a term not to be bandied about. It’s accurate, I think.

One of the signal events of Pym’s life as a writer was her publisher’s decision in the early ‘60s to stop publishing her. Despite having a loyal and small-but-significant fan base, she was deemed too old-fashioned and not enough of a money-maker. She took the blow in her usual stride, saying all sorts of stoic and very British things, but I know she must have been heartbroken. Her rejection at the hands of money-hungry publishers is emblematic of the contempt in which artists are held and with which many writers I know are sadly familiar.

Rejection notwithstanding, she kept writing and enjoyed a measure of success and redemption before her death in 1980. Now she is my hero. She reminds me not to give up and to take setbacks with grace. (I may not be very good at this last one.)

Sometimes I wish I had Kim Kardashian’s ass (which really is spectacular). But I’d settle happily for Barbara Pym’s stiff upper lip.

Monday, February 22, 2010

Remembering Eight-Year-Olds

Today, while taking a walk around my neighborhood, I passed a driveway on which two eight-year-old girls were clutching the passenger-door handle of a Honda Accord and shrieking. They appeared to be playing a game.

It has been twelve years since I’ve had an eight-year-old.

The experience made me remember so many things I’ve forgotten.

To wit:

--Eight-year-olds like to yell for no reason;

--They are loud even when they are not yelling;

--They are always hungry for what one doesn’t have in the house;

--They are unafraid to tell one how deficient one’s selection of snacks is;

--Their games do not look interesting to adults;

--There is nothing more exquisite than being at a friend’s house after school;

--It is very, very nice to have a friend over after school, but slightly less nice than being the guest because of family-member-related anxiety (little brothers who insist on being included; mothers who buy bad snacks);

--Eight-year-olds never want to go home (unless they are on their first-ever sleepover and it is 2 AM and their parents will not answer their phone);

--Eight-year-olds have no fashion sense;

--Eight-year-olds may or may not be interested in talking to the parents of their friends, but if they are not interested, it is usually because they are shy and not because they think parents are too hideous to live.

I miss eight-year-olds.

Well, I miss my own.

It has been twelve years since I’ve had an eight-year-old.

The experience made me remember so many things I’ve forgotten.

To wit:

--Eight-year-olds like to yell for no reason;

--They are loud even when they are not yelling;

--They are always hungry for what one doesn’t have in the house;

--They are unafraid to tell one how deficient one’s selection of snacks is;

--Their games do not look interesting to adults;

--There is nothing more exquisite than being at a friend’s house after school;

--It is very, very nice to have a friend over after school, but slightly less nice than being the guest because of family-member-related anxiety (little brothers who insist on being included; mothers who buy bad snacks);

--Eight-year-olds never want to go home (unless they are on their first-ever sleepover and it is 2 AM and their parents will not answer their phone);

--Eight-year-olds have no fashion sense;

--Eight-year-olds may or may not be interested in talking to the parents of their friends, but if they are not interested, it is usually because they are shy and not because they think parents are too hideous to live.

I miss eight-year-olds.

Well, I miss my own.

Tuesday, February 16, 2010

Citius, Altius, Fortius

We have been watching the Olympics.

For many years, I hated the Olympics, mainly because they require the participation of people who are good at sports. People who are good at sports tend to be people with whom I have nothing in common. They are, in my experience, optimistic, driven, headstrong, persistent, and indefatigable. I (gloomy and lazy, with notable expertise in sleeping and giving up easily) prefer the company of my own kind.

I am the sort of person who is not fun to watch the Olympics with if one enjoys watching the Olympics. I am always making comments about how figure skaters are anorexic whether they know it or not, how snowboarders were probably in the slow-readers group in elementary school, how Americans’ adoration of athletes as heroes is disgusting and tiresome. Why don’t we clap and cheer for teachers and nurses? I am always wondering aloud. Robert nods in weary agreement, straining to hear the sportscaster. (Really, it is a wonder he hasn’t put a blanket over my head and locked me in the linen closet. If there were an Olympic medal for patience, he would win it.)

This year, while I continue to whine ceaselessly (about the Chinese figure-skating pairs’ oddly antiquated music, about elite athletes’ lack of a healthy childhood, about Bob Costas), I am finding myself moved and exhilarated in a way I’ve never been before. What I’m seeing, as if for the first time, are the grace and beauty of human beings pushing themselves to do things they shouldn’t be able to do. In a year in which I’ve endured quite a bit of illness, I am newly appreciative of healthy, vibrant, intact bodies urged to extraordinary heights.

It’s not as though I’m suddenly a different person. I’m not going to stop thinking that we’d be better off as families/communities/societies if we spent more time applauding intelligence and decency and less time measuring just how fast Junior can ski down a bumpy hill.

But maybe I’ll marvel just a little at the things we humans can do when we set our sights on distant goals. Maybe I will try to bring a little of that persistence and stick-to-it-ive-ness to my own life, my own battles. Maybe I will secretly cheer when the apple-cheeked American crosses the finish line first.

Just don't expect me to stop complaining. For one thing, those uniforms. I mean, come on.

For many years, I hated the Olympics, mainly because they require the participation of people who are good at sports. People who are good at sports tend to be people with whom I have nothing in common. They are, in my experience, optimistic, driven, headstrong, persistent, and indefatigable. I (gloomy and lazy, with notable expertise in sleeping and giving up easily) prefer the company of my own kind.

I am the sort of person who is not fun to watch the Olympics with if one enjoys watching the Olympics. I am always making comments about how figure skaters are anorexic whether they know it or not, how snowboarders were probably in the slow-readers group in elementary school, how Americans’ adoration of athletes as heroes is disgusting and tiresome. Why don’t we clap and cheer for teachers and nurses? I am always wondering aloud. Robert nods in weary agreement, straining to hear the sportscaster. (Really, it is a wonder he hasn’t put a blanket over my head and locked me in the linen closet. If there were an Olympic medal for patience, he would win it.)

This year, while I continue to whine ceaselessly (about the Chinese figure-skating pairs’ oddly antiquated music, about elite athletes’ lack of a healthy childhood, about Bob Costas), I am finding myself moved and exhilarated in a way I’ve never been before. What I’m seeing, as if for the first time, are the grace and beauty of human beings pushing themselves to do things they shouldn’t be able to do. In a year in which I’ve endured quite a bit of illness, I am newly appreciative of healthy, vibrant, intact bodies urged to extraordinary heights.

It’s not as though I’m suddenly a different person. I’m not going to stop thinking that we’d be better off as families/communities/societies if we spent more time applauding intelligence and decency and less time measuring just how fast Junior can ski down a bumpy hill.

But maybe I’ll marvel just a little at the things we humans can do when we set our sights on distant goals. Maybe I will try to bring a little of that persistence and stick-to-it-ive-ness to my own life, my own battles. Maybe I will secretly cheer when the apple-cheeked American crosses the finish line first.

Just don't expect me to stop complaining. For one thing, those uniforms. I mean, come on.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)